Audio:

The words “I need my life back” came deep from within the soul of Kenny Bontz. The flamboyant American, who hails from New Jersey, is chiselled from a different kind of rock. Get past the mohawk, beyond the confident walk and cut through the hard man exterior, and you will find a man who has experienced the pressure of disease, felt the heat of addiction and who has emerged on the other side, shining like a precious diamond.

Today, Kenny finds his life fulfilling as he works through the process of becoming the best version of himself. Without valleys, there can never be peaks, and Kenny needs those highs. It is in his character. Kenny says that “life deals you the cards and you’ve got to play ’em; sure there are times when you want to fold, but if you keep the hand then eventually you can trade a few.” Kenny’s story is one of turning his original cards into aces.

Parents John and Marion encouraged their son to play all sports. He didn’t have to be told twice, baseball, basketball, soccer or anything that involved a ball was right in the zone for sports-mad Kenny. By 11, Kenny was diagnosed as having Brittle Diabetes, a form of type one diabetes that sees the blood sugar levels rise and fall dramatically. By 19 years of age, Kenny was working with his father in the family printing firm, when an accident took him to the emergency room. The initial diagnosis was incorrect, and after a month of rehab, Kenny returned to the hospital when swelling around his knee reappeared. On this occasion, the clinicians found evidence of Ewing Sarcoma in his leg, a cancer of the bone.

The hard-living 19-year-old was devastated, “I called it the C word. You know, because, when you mention that word, it goes along with death. I was old to get that type of cancer, as it is normally found in younger children. Being 19 and also being a type one diabetic, my chances weren’t too good. But I’m a fighter.” Kenny is ever thankful to Dr Paul Myers who helped save his life. After three cycles of chemotherapy and surgery, Kenny was soon back on the soccer field, but this time coaching little kids. One day, he was clowning around with the youngsters, and a mistimed tackle from one had Kenny back in the hospital for a replacement cadaver bone. “When they replaced it, my leg was so swollen they couldn’t close it. So they cut my femur head off the top of my knee and the tibia head off the lower part of the allograft and gave me a total knee replacement.”

Kenny was all into life, walking, motocross, golf and soccer. The 15 years life expectancy of his knee replacement was going to be challenged to the full. Sure enough, six replacements in just nine years followed. Every time he would have to go through an operation, and every time he would have more pain medication, “The anaesthesia wasn’t as bad as the pain meds. Anaesthesia knocks you out, but a lot of my operations were done with a local anaesthetic, so I was awake for most of them. They give you a sedative, and you fade in and out. But when I would come out of the operation, they would hook me up to a drip. That’s where the addiction started, because those drugs, oh my body loved ’em. Over some time, with the pain I was in, I needed more pills and more alcohol. I started out with three pills a day, and then for six years, I took Vicodin 800 milligram pills every day. I would take 80 pills every day, so that’s 64,000 milligrams per day, together with a lot of alcohol and some other things.”

Kenny was good at hiding his addiction and says that most addicts are. His morning routine started around six o’clock, “I would take twelve, 800-milligram pills just to get out of bed. I’d chew them like candy. I wouldn’t even take water with them. By 10 o’clock I was having a couple of beers, and here I am in this vicious cycle, pills and booze. If there was a stronger word than vicious I would use it, because you don’t realise what it does to you at that point. It is brutal.”

Kenny realises that his opioid addiction cost him his marriage. The people close to him knew what he was doing, but not to what extent. He was even able to hide it from his doctors and still was able to get prescriptions for more and more pills. Commonly he would be prescribed 500 pills every week. Pain meds, antidepressants, anti-this and anti-that types of medications can be very addictive. When used correctly, they can be lifesavers, but a widespread misuse is well documented. “When I was a kid, none of my friends had ADHD medicine, but now it just seems like they classify people with these problems and guess how they fix ’em? Just give them some pills. That doesn’t work, I mean it’s a bad epidemic. I had an opioid problem before the opioid problem happened in the US, I was a major addict back then.”

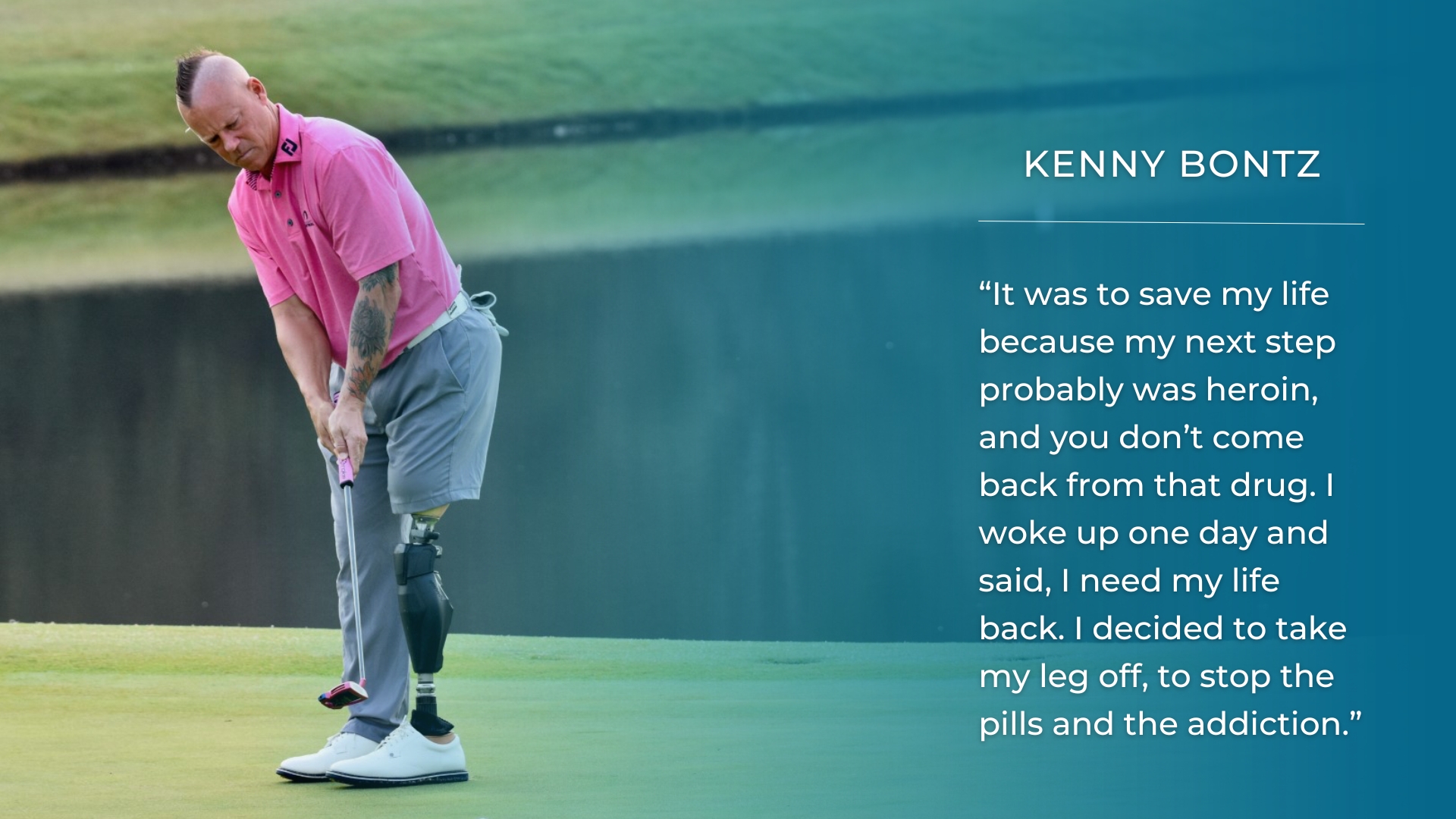

Kenny says that what happened next was the easiest decision he had ever made in his life, one that would give him a new life. “It was to save my life because my next step probably was heroin, and you don’t come back from that drug. I woke up one day and said, I need my life back. I decided to take my leg off, to stop the pills and the addiction. I had my surgeon take it off. It was a 15-minute operation, and I woke up with a Dilaudid drip in my arm.” Kenny instinctively knew he had to stop the meds, after all his elective amputation was the first step, but there was much more to come. “That drip had to go, I had my leg off for a reason and so ripped the needle out. My rehab started that day.”

In the recovery room, doctors and nurses were pleading with Kenny to get back on the drip. His mind was made-up, no more meds, “I was in a lot of pain, it was excruciating, not something you can put on a scale of one to 10. But that’s how my mind works with things. I could deal with it because I knew, I’d get through the day. I have a saying that ‘every day that passes is one less day, I’ve got to go through it.’ I’ve built my life on that.” His family and friends knew that he was making changes, but just not how radical those changes were and that he was going ‘cold turkey.’ “It was bad. The shakes, sweating, throwing up and excruciating torture. I had weeks of deep tissue massage to break-up the crystallisation in my muscles that came from the pain pills.” Three and a half months later and the brain fog he had been in started to clear. Kenny could begin to see a new future.

It is said that the night is darkest just before the dawn, and for Kenny, although he faced new challenges he did so with a clear mind and healthy body. It was now time for a prosthetic leg. Typically Kenny thought that he would simply put one on and start his life again. Think again. “It didn’t work like that because my thigh was probably the size of my forearm. It was effectively a bone wrapped in skin, because it was so atrophied. Then it would swell to almost the size of my waist. So you go through the shrinking, the swelling, the shrinking, the swelling. I didn’t know that before the operation. Probably they told me but I chose not to listen to it. I had in my mind how it was going to work, and didn’t realise the processes you have to go through.” Together with his trusted companion, Maximus, a Rottweiler that Kenny had bought to help him get active, they made great strides. Within three years Kenny was back to walking again in the right way.

As Kenny walked out of a courtroom, following his divorce, his ex-wife Amanda said, “You need to change yourself if you’re ever going to meet anybody.” Those words had a profound effect and caused him to reflect on his life. He called a couple of friends and arranged to go out for dinner. He posed them a direct question, “Do you think I’m tough? I mean that in a bad way. Am I sometimes a nightmare?” No one would say anything. Finally, one of his friends broke the silence, “Yeah, you’re very rough. We all have families, and when we go out with you, we never know if we could end up in jail.” That really hit home with Kenny and he took a step back and sought help, “The woman peeled me like an onion, and I love what I’ve found. I call it the old Kenny and the new Kenny. The old Kenny was a nightmare, but being from New Jersey probably didn’t help. I now realise that I made a lot of people frown throughout my life for 46 years. For much of it, I was high as a kite on the meds.”

Golf had been in Kenny’s life before his amputation. A two handicap golfer who would play with his buddies and compete. Competition is something that Kenny thrives on, be it against others or against himself. He would be just as tough on himself as he would be on others and openly admits that he didn’t respect the game. How could he, as he didn’t even respect himself? Today the new Kenny respects the game, his playing partners and himself, “It’s like a domino effect. I love the game so much now. I’ve come a long way, and people are amazed that I did this without any help, but that’s me, not many people are built like I am. I made a decision, and I stuck to it to save my life. There’s no way I’m going back to doing any of that.”

Tough certainly, respectful definitely, grateful undeniably, Kenny’s appreciation of the role he has to help others has grown. The new Kenny turned 46 years of age and vowed to make someone smile every day. It is only three years since he made that decision, but it is his new addiction. “It works great for me, and it works great for other people. That’s what I’m about now. I mean, golf is great. I love it. I’m outside, I’m enjoying it. But my goal now is to kind of pay it forward and help people. It’s heartwarming to me. I mean, that’s why I do it.”

The soul is like a rough diamond, and for Kenny, the pressures of disease, amputation, the intensity of addiction, his rehabilitation and polishing of his character through introspection, enabled a new Kenny to emerge. He is acutely aware that everyone will have roadblocks and potholes to negotiate along life’s journey. Kenny looks back to those days in chemotherapy, “Everyone told me that the chemo was working, then they would leave, and I’d be sitting there and asking myself, what if it’s not working? What if I’m dying? That’s how your brain can work and so you have to retrain it to become a positive tool. I never used to read books. Now I read a lot of books, do a lot of meditation, and that helps. It just mentally frees you up, and you need that because life is hard enough. I mean, you have to want to get better, and you have to better yourself.”

Kenny is pursuing his dream of playing on the Champions Tour. As the first US player to break into the top 10 of the World Rankings for Golfers with a Disability in 2019, he is on his way. “Golf, it’s my life now. It means a lot to me. I want to be the first amputee to play on the Champions Tour. I want to be a breakthrough guy. He relishes his opportunity to influence some of the new players coming into golf for the disabled. As an established player, he has their attention, but it is the attention of the wider golfing public that he intends to attract, “I want to go out and showcase my talent, have people say, wow, that guy from the States with the mohawk, you know, he can play. Hopefully, it will draw some attention to, and let them see these guys playing with all abilities, that they can do it.”

Kenny has taken ownership of the cards in his hand. He realises that some were dealt as a matter of chance, others he selected by choice. Today he is making trades, changing his hand to allow him to live the way he wants, to pursue his dreams and to make a difference.

Contact EDGA

NB: When using any EDGA media, please comply with our copyright conditions