Founder of the United States Disabled Golf Association, Jason Hicks Faircloth talks with Tony Bennett about his life growing up with cerebral palsy. It has happened to all of us at one time or another. You are in your backyard, and your attention is on whatever it is you are doing at that moment, reading a book, doing a spot of gardening, or swinging a golf club, oblivious to anyone else, lost in the moment. Little did Johnny Paterson realise, as he hit one ball after the other, that he was quietly planting the seeds of golf in a young man who would develop a passion for the game that would take him to the home of golf, St Andrews in his quest to learn more and quench his thirst, at least temporarily.

Jason was watching Johnny closely from next door, taking in the scene, building a picture in his mind of what a golf swing looks like and preparing his own pattern of movement that would serve him well. Jason is living proof of the age-old adage ‘never judge a book by its cover.’ The cerebral palsy which Jason lives with is very noticeable, “It affects every part of my life, including my speech,” he says, “I was told that I may never walk or talk, and so from early on it was clear that it was a pretty bad case.”

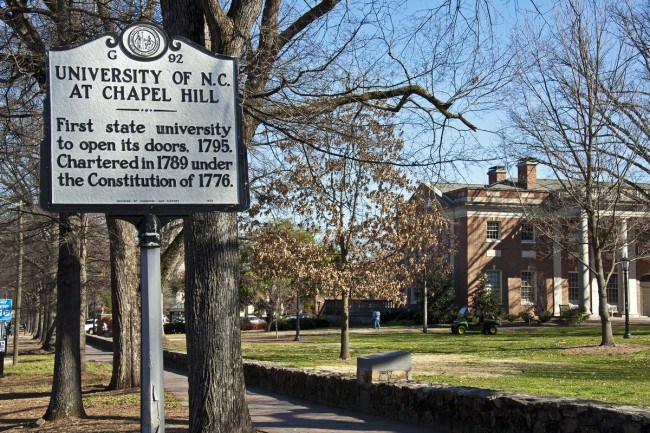

To understand Jason it is essential to get a feel for what he has endured over his 39 years on planet earth. Born in Clinton – North Carolina, he became the younger brother to his sister Catina and son to his loving parents Hicks and Mylinda. “mom and dad took me to physical therapy and occupational therapy three times every week. Every time it was hard, I was made to wear a cast, then it became leg braces, all of which was to help maintain the muscles in my legs in the hope that they would stay straight and not curve,” says Jason. “We would visit Dr Greene at the university of Chapel Hill a few times a year until my senior year of high school, and the effort my family put in was never-ending.” The relentless schedule of therapy sessions also included regular speech therapy, to help Jason talk, “They put peanut butter in my mouth to help develop the muscles I needed to be able to speak.” Jason understands the sacrifices that his family made and says, “If it hadn’t been for mom and dad, I wouldn’t walk or talk to this day. Lots of hard work on everyone’s part has allowed me to do both,” for which Jason is very grateful.

An understanding family and close circle of friends can be a place of sanctuary for many unwilling to face the world. Jason, however, is cut from different stuff and says, “Unfortunately you cannot control what everyone thinks but you can through your actions try to help them to understand. I think people see how it [CP] affects me, it’s an obvious impairment, but I just go out and live life and do everything the other guys do. I honestly think that this is the best way to teach others.” Challenging poorly formed perceptions seems to drive Jason, who explains that the first reaction of many is to think, “look at this ‘poor guy’, he can’t do anything. That happens a lot, I can see it on their faces.” Jason thinks that this is the most frustrating thing to deal with, “I believe that having a speech issue is another problem that is often overlooked. Unfortunately, they look down on me as being dumb and not being capable of doing much. It’s just how it is. So I have to do much more work to get things done or to even get people to listen to me than the average person.”

The seeds that his neighbour planted started to germinate when his friend Brandon Williams began to play, and it was during his high school years when Jason really got the golf bug. Lakewood high school had a golf team and Jason played as the number three in both his freshman and sophomore years, before settling in at number four in his junior and senior years. After high school, Jason earned an Associates Degree in Business Administration from Sampson Community College, but it was golf that was calling. “Sometimes I am not that good at golf, but at least I say so, you won’t find me sugar coating it,” says Jason who explains how the cerebral palsy affects his game, “I have always thought I should swing and make the movements like everyone else and so it’s difficult to handle my expectations sometimes. Every day I’m learning that my muscles don’t work the way that they are supposed to. Some of my muscles have not fully developed, especially in my legs and even some of my neck muscles, which I find odd. Some people go to work for money – I go to work just to be able to walk, this is a big difference in mindset.”

Jason definitely sees golf as being part of his life work. It seems that he is always on the lookout for ways to contribute and learn more. He has a history of contribution, and in 2001 he volunteered for both the US Open and US Women’s Open, where Retief Goosen and Karrie Webb took home the trophies, “It was great to see how they prepared for the championships. I got to work with the caddies and could see them joke around off the course. I love seeing what goes on behind the scenes the most, it is very different than just being a spectator,” says Jason, who was back to volunteer in 2005, 2007 and 2014 versions.

Jason uses such opportunities to learn about himself, “I’m very competitive, which I knew beforehand. I’m trying to be more laid back, get over bad shots quickly and move on, but It is still a learning process,” says Jason. In 2011 Jason made a huge personal commitment that changed the way he looks at impairments, “I had never really considered competitions that were only for people with a disability until the Disabled British Open in St Andrews caught my attention. I saw how big these type of events really are. Luckily I was smart enough to realise that it was a big deal and so looked into it, and honestly, I am glad as it changed my entire thinking.” 88 golfers competed in the 2011 Disabled British Open and Jason came in at 6th place in his category and in 32nd place overall, “I didn’t stay for the awards ceremony which I later regretted, but when I returned in 2012 to play I promised myself that I would stay, needless to say, I came in 2nd.”

Jason is using his experiences to help others, “I think people with disabilities have been given the wrong advice for a long time. Mainly I’m talking about off the course, and it saddens me that a lot of people don’t yet take control their own life, but if they don’t learn how to, then, when they get older, it can be a real problem. I advise people that they can always do more than they think if they just believe.” Jason is equally strong with his advice when talking about golf, “You just have to go out and do it. If you have a disability and want to try golf, we’ll just get to the course or driving range and start asking questions. I can tell you that if you wait for some trained person to come over that only works with disabled players, then you probably will not ever get started in golf. Look, we know there a lot of golf professionals and organisations who focus on providing clinics and training specifically for golfers with impairment, this is needed and highly recommended.”

“We have steered a lot of new golfers to these programmes, and they are popping up all across the USA, but unfortunately, the ‘disabled community’ has been taught that they should look for programmes just for those with a disability. That’s sad, but it’s the type of thinking that most families have in their DNA,” advises Jason. “After I came back to the US from the Disabled British Open, I started to see that the USA hadn’t run a tournament like this, and so that was the beginning of the United States Disabled Golf Association.” It took several years for Jason to organise the first United States Disabled Open which was played in May 2018 and he attracted 48 golfers, Jason says that it is “My intention is to model the tournament on the Disabled British Open, and my goal is to make the championship one of the best in the world.”

Remember the next door neighbour who was in his own bubble swinging the club and hitting balls in his yard? What would have happened if he had been pitching a baseball or shooting hoops? Would Jason Hicks Faircloth have found the game, which has become his purpose? I would like to think so, but in any case – thanks, Johnny.

Jason’s Videos:

Contact EDGA

NB: When using any EDGA media, please comply with our copyright conditions