Audio:

Sometimes the kindness of one stranger can make all the difference.

Steve Crocker had loved sport in his younger days, and he had been highly active as an engineer on ships in the UK’s Merchant Navy. Ever since being a kid, he had been kicking, catching, and running on the sports field, or sailing, swimming and canoeing in the sea off the coast of his native Cornwall.

However, his fitness and strength as an adult masked a gradual degeneration of his spine, and by the age of 39, mysteriously he was scuffing his shoes walking to work, tripping on kerbs, and struggling to lift his feet. A shocking diagnosis led to complicated surgeries, long rehabilitation and the increasing threat of a life ahead using a wheelchair.

Depressed, he completely gave up on sport, and tried to develop an interest in looking at architecture and ancient churches.

Then a few years ago, he happened to treat his then partner to a trip to watch a women’s professional golf tournament, and the kindness of a stranger changed Steve’s life.

“I met Graeme Robertson. It was one of the Ladies European Tour events at the Buckinghamshire in 2015, and he got talking to me and said, ‘Oh hello, I’m Graeme. I’ve got MS.’ And we had a really good chat and he said to me, ‘Come along and play the golf for disabled,’ which I’d never heard of.

So I had to get over my depression, and that was Graeme Robertson really, actually meeting him and listening to him. Nothing was too much trouble for that man. He could barely move, but he didn’t quit.”

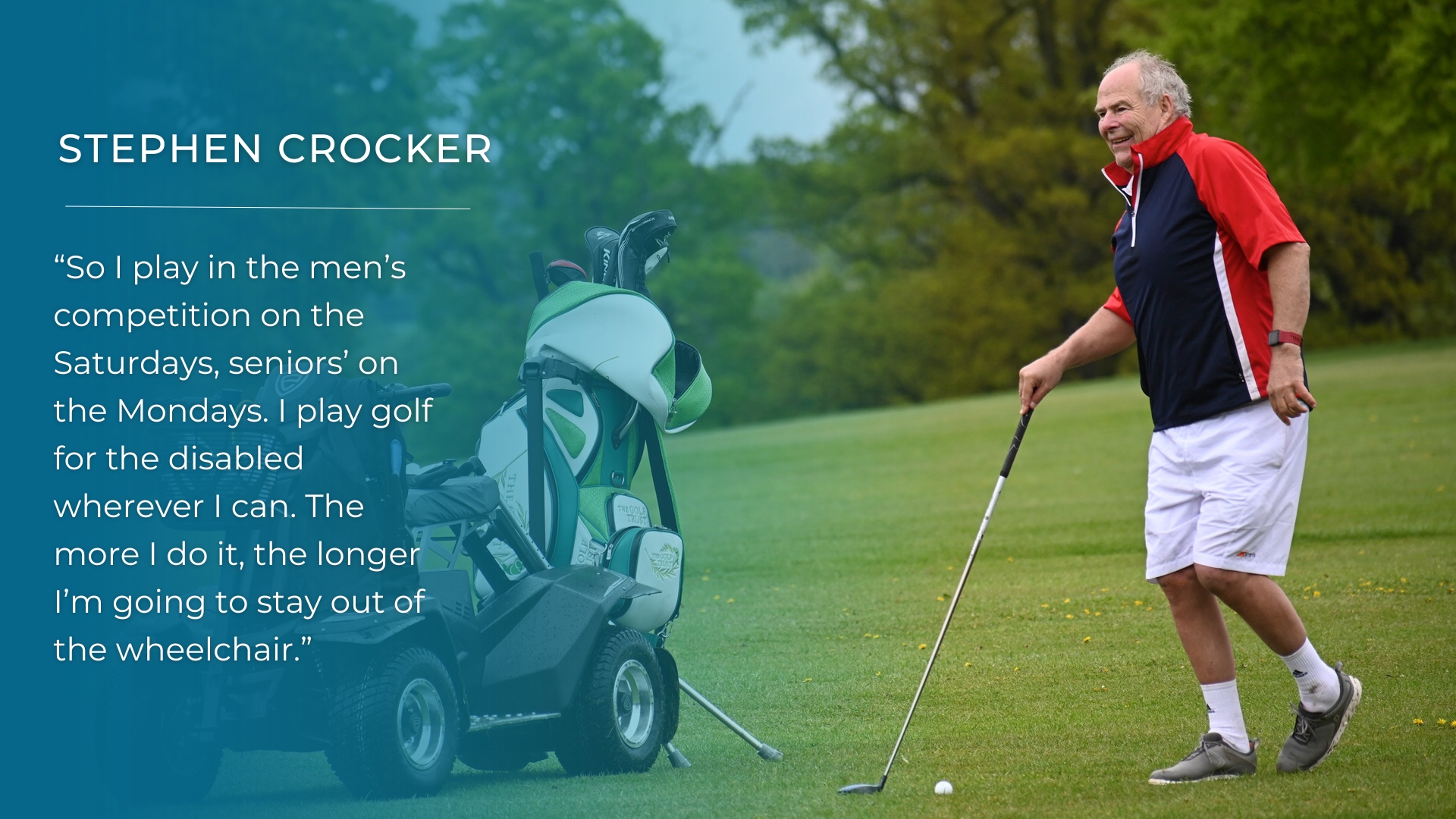

Steve adds: “Starting from that first competition in 2016, it’s now get out there every single opportunity I get. So I play in the men’s competition on the Saturdays, seniors’ on the Mondays. I play golf for the disabled wherever I can. The more I do it, the longer I’m going to stay out of the wheelchair.”

Today Steve is 65 years old. So far in 2022, his competition schedule has included the EDGA Johnny Reay Classic in May, where he exuded warmth and a generous spirit when meeting the EDGA volunteers; he and fellow players were key to a great social vibe at the Coventry event. Steve then took his positive outlook to the German International in Bavaria two weeks later and the following week to Turin in Italy, to play in the Italian Open; which were also EDGA badged events. He uses a single-seater buggy to travel the course and look after his legs and back, and says that through playing golf he feels better than he did 10 years ago.

This true sportsman was always a strong man, hailing from the little fishing port of St Agnes not far from ‘Land’s End’ in Cornwall, England. He joined the Merchant Navy after a five-year apprenticeship at Devonport Naval Base. Steve served for 11 years as an engineer. He loved the worldwide travel, with Japan, Sumatra, Malaysia, and Polynesia being his particular favourites.

On his return from globetrotting he worked for a while before signing up as a mature student, aged 36, at the University of Sussex, to study mechanical and manufacturing engineering.

Golf was only on the very edge of Steve’s consciousness in those days, though he had played nearly every other sport as a growing lad. Rugby, football, hockey, orienteering, rock climbing, cross country running, sailing, canoeing with the Sea Scouts, even ‘Tug of War’ and boxing.

“I just loved it, absolutely loved it. I couldn’t sit still. And when I got older, I obviously wanted to be a professional sportsman because you’d be in the gym at least four times a week, plus you’re playing sports Saturday and Sunday as well. It was just an obsession more than anything, but I never quite made it, unfortunately.”

So how did golf arrive for the first time?

“Goodness. Probably when I was at university as a mature student. My eldest son was about four at the time, and we used to go to a pitch-and-putt along the seafront at Brighton, and he just used to love hitting golf balls. So we got him an old 3-iron and cut it down. And then I started taking him to a driving range, where we shared a few lessons with a PGA Pro, but that was really the only golf I tried.”

Steve adds: “For me, it was one of those company executive type sports, or for the likes of James Bond. For working class guys like my father and myself, it just didn’t come onto the radar at all.”

Besides, after university, Steve was busy in a new job in London. At the age of 39 his travel into work was starting to get trickier.

“I was living in a place called Preston Park, which was just a short walk away from the station there, and I kept tripping on zebra crossings and kerbs, and it was getting to the point where I was having to put my hands in my pockets to lift my legs up.”

At this time, Steve was taking his son to see a cranial osteopath following a traumatic birth, which had inhibited his speech development. The therapist succeeded and got the young boy talking properly. This remarkable result would lead to a different discovery.

“The osteopath said to me one day, ‘What’s the matter with your legs?’ And I just said, ‘I don’t know. I’ve been having trouble walking lately.’ He said, ‘Oh, just jump up on the table. I’ll give you a quick exam.’ And he started examining my cervical spine with his fingertips, and he said to me, ‘Well, I’m going to call your GP right now. You’re going to have to go to him, and then go up to the hospital and get an MRI.’ He said, ‘There is something seriously wrong with your cervical spine.’ That was a bit of a lightning bolt. And so I went up there, had the MRI. I think within three hours, it was all on the same day. I had a diagnosis to say that my cervical spine was getting compressed in three places.”

Steve speaks of being “completely shell-shocked” with the diagnosis of Spastic Paraparesis after a lifetime of sport and exercise. His C3 to C6 vertebra were squeezing the discs onto the spinal cord. He needed a laminectomy (removing a portion of vertebra called the lamina, which is the roof of the spinal canal) – a 14-hour operation followed by nine months of recovery, with physiotherapy three or four times a day.

“It was kind of a monster of an operation. We were hoping that things were going to get back to normal, but they never quite did. And I think it lasted for about seven years, and then it started getting bad again and I started tripping over things, and it happened again. So they went back in a second time, with the same results. It almost got better, but not quite, but then it really went downhill quite badly after that second operation.”

A third major operation would follow, but today any procedure would just be too risky, as the spinal cord could be damaged irreparably.

“So yes, it’s one of those things, it’s just chronic, it’s progressive, and yes, I’ll just end up in a wheelchair.”

Steve had developed rheumatoid arthritis after the first operation. In those times, he fought hard to help himself, trying Pilates, yoga, the Alexander technique; trying to find mobility and flexibility.

He recalls: “And basically I gave up, I think after the third operation, and didn’t do anything for six or seven years.”

It was then he started looking at the churches and architecture, trying to engage his brain as his body was failing him. But then one day in 2015 he took his then partner to a Ladies European Tour event at Buckinghamshire Golf Club to have a look at something new.

On parking their car, the tournament organiser noticed them and was incredibly encouraging, lending the couple use of his buggy to get about, finding them a prime spot on the first tee to watch and even introducing them to the players.

And of course when we came back, I was having a go on one of those putting things in the spectator village, and Graeme Robertson came up to me and tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘Oh, hello, I’m Graeme. Do you play golf at all?’ I said, ‘You’re joking, I’m disabled.’ He said, ‘No, no, no, let me have a little chat to you about our Disabled Golf Association.’

Graeme is one of those few people who you will ever meet in your lifetime who will give you a lot of time and all the help that he can.”

Graeme Robertson, who has Multiple Sclerosis, is a leading light of the Disabled Golf Association (DGA), an England-wide registered charity with a focus on providing golf competition days for people with impairments and disabilities.

“But nothing was too much trouble for that man. He could barely move, but he didn’t quit. And when I met him at that golf tournament I thought, ‘Wow. If that fellow can do it, so can I.’ I just loved it when I went and started hitting balls. Yes, okay, it was a bit wayward, but I think I only had about five clubs. I didn’t have a wood or anything. I think the biggest club I had was a five iron. It was just enough to keep the ball going up the fairway.”

Steve adds: “Because it was late in the year when we had met, I think I started to play in April 2016, and I ended up with about 120 on my first scorecard. But I had such a good time. I loved it, absolutely loved it. Just being out doing something, meeting a lot of people with disability, and yes, I was absolutely hooked from that first time. I think I ended up with something like a 28 handicap after a couple of events, and I managed to get that down to about 20 by the end of that season.

“I think originally I had zero expectations. It was just turn up, swing a few clubs and see how you get on. But of course the better you start to strike the ball, you think, ‘Now that I’ve broken a hundred, my next goal is to get down to 90.’”

The scoring, testing yourself, is often a big thing for golfers, but Steve is also in no doubt of the other benefits to his wellbeing; being out there with other people, enjoying the fresh air.

But I think the first thing is, the major thing was depression. Just absolutely getting over that depression, because that’s an absolute killer… and can be the biggest hurdle for the disabled.”

Taking up golf with a disability in his late fifties, Steve looked around for a suitable golf club. Unfortunately, at first he found little encouragement, as the clubs were nervous about, amongst other things, how long it would take to play, and whether he would hold up the members.

“And it was only the owner down at Horam Park [East Sussex] who said, ‘Regardless, forget it. No worries. Sign here. That’s fine.’ And he was really generous as he said, ‘Every time you play, we’ll give you the use of a buggy, and you won’t have to pay extra for it.’”

Steve says he loves being part of Horam Park, he enjoys a lot of ‘mickey-taking’ back and forth with his friends there, and is highly appreciative of the support he enjoys from his fellow players… who he loves to outscore whenever he can.

“Yes, absolutely. There’s nothing better being a disabled person than beating able-bodied people. Coming in with a better score on your card. You know, if you actually hit one off the tee, and if I catch one, I can still get past most of the older guys down there. The single figure handicappers are putting it way past mine, but normally I’m still making about 200, 210 [yards] from the tee. So yes, if I can just keep it on the straight and narrow, I’m right in the mix.”

Side-hill lies and deep bunkers are a problem for Steve and he endures plenty of falls to the ground, sometimes amusing for his playing partners and himself, sometimes much less so, but he keeps getting up, and like his friend Graeme, he never quits.

Coaching Steve in his swing is Cae Menai-Davis, a PGA Professional based at The Shire near London. Menai-Davis is also co-founder of The Golf Trust, a charity set up to bring people together through golf. The Trust’s work in community spaces is helping to make golf a more inclusive sport for all.

Not only has Cae helped Steve’s golf game but the Cornishman was proud to put the Trust’s logo on his golf bag and to be an advocate for the charity, promoting its community golf message wherever he travels. Steve is now keen to organise a local project to support other golfers with a disability. Covid-19 has got in the way but he remains determined to set this up when he can.

“But as I say, I’m still determined to try and stay on my feet for as long as I can. I think as far as golf goes, I don’t see my life away from it now… I’ve always wanted to give something back. After the first couple of years of disabled golf, it’s transformed me from what I used to be to what I am now.”

He adds: “You don’t have to be Tiger Woods or Nick Faldo. It’s meeting people, having a little bit of fun, a little bit of exercise, just getting out of the everyday run of things.”

When asked about any advice he might give to others Steve jokes that he certainly wasn’t the best person to ask about this when he was travelling around looking at old churches. But he says that mentors really can be invaluable and he mentions Graeme, Cae, Mike Overton in Wales and Jim Gales in Scotland, all of whom he has seen supporting others so well.

“But actually, anybody who plays disabled golf, because I think they’re all mentors to some extent, as they all go home and say, ‘I’ve just had a few good laughs. You want to come along to the next one?’”

Today, Steve is battling with his health and fitness to keep his legs moving okay, so he can still stand to swing a golf club, but he has enjoyed some positive recent encouragement. His new therapist works with a programme called ‘Be Activated’ and Steve has enjoyed striking results after treatments. A lot of small changes have made a profound overall effect, he says. Client and therapist have created future plans and goals with a long-term aim of 50% improvement. “We disabled folk need these targets to aim for,” says Steve, who is delighted with progress.

Meanwhile, Steve will continue to encourage as many other people with a disability to try, or get back into, the sport he found himself, probably in his case just in time.

“If I can make one person happy, if they can change like I did… The sense of wellbeing I got after that first game of golf; I know I talk 19 to the dozen, but I haven’t got the words about how good I felt when I came in from that golf. I was absolutely shattered. My legs were aching, my back was aching, I didn’t know what to do with myself physically. But I just felt so good afterwards. Just getting out there and just having some fun. And you will make lifelong friends too!”

Contact EDGA

NB: When using any EDGA media, please comply with our copyright conditions